Medical and pharmaceutical packaging: some clearer priorities

For the more fortunate among us, the only knowledge we have of the current state of intensive care units (ICUs) in our major hospitals will have come from the stark imagery on our TV screens and social media feeds.But those images are likely to be among the most enduring to emerge from what is now a global novel coronavirus pandemic, underscoring as they do the dedication and bravery of frontline medical staff and the paper-thin resilience of even our most advanced medical knowledge in the face of unfamiliar threats.

In this emergency setting, the focus has quite rightly been on the availability of ventilators, personal protective equipment (PPE) and the deployment of trained personnel. But there are potential packaging angles even in this healthcare crisis and, over the months and years to come, researchers working in this area could be grappling with some of the challenges it has thrown up.

While the detail may not yet be clear, and will differ in any case from country to country, certain areas of concern appear likely to emerge.

Emergency care

At Cal Poly in the US, Javier de la Fuente explains that, although the human-factor implications of medical packaging extend well beyond openability and accessibility, these are critical considerations. “Mobility, dexterity and visual acuity are affected by having to wear medical gear, no doubt about it,” he says. “Some companies design with that scenario in mind, many others do not. You’d be surprised.”

At Cal Poly in the US, Javier de la Fuente explains that, although the human-factor implications of medical packaging extend well beyond openability and accessibility, these are critical considerations. “Mobility, dexterity and visual acuity are affected by having to wear medical gear, no doubt about it,” he says. “Some companies design with that scenario in mind, many others do not. You’d be surprised.”But that disparity, he proposes, is precisely why - in terms of pedagogy - design-thinking needs to be an integral part of university packaging programs. “That way, future packaging engineers can empathise, by default, and predict situations in advance.”

Cal Poly has had a design-thinking approach embedded in its packaging development teaching for the past six years, he says.

De la Fuente’s own research has focused on the importance of packaging affordances and design-for-intuition, relating this focus to these types of emergency healthcare environments where mental stress, fear and sleep-deprivation can all play a part. “All three factors significantly reduce reading and concept comprehension,” he points out. “If a user falls into just one of these categories, can you imagine how his or her ability to complete tasks is going to be impacted?”

His focus on affordance-based design methodologies has been shared by Laura Bix at Michigan State University (MSU). Quite apart from the broad ‘lessons’ of the current crisis in terms of proactive problem-solving, long-term thinking and collaboration “across roles, borders and disciplinary silos”, she believes it has highlighted some more specific issues. “It certainly reinforces the importance of a well-oiled supply chain and the sterile delivery of packaged products,” Bix says.

Ambulance paramedics

As reported last month, rather than the ICU, some of her recent work has focused on a different emergency health setting: the work of paramedics in the back of a moving ambulance. This research, which simulated a speeding ambulance inside a lab, helped to bring one key principle of package design into sharp relief, she says: “The context surrounding the person using the product matters.”

The background to this study, says Bix, is evidence suggesting that patients brought in for treatment in an ambulance are more likely to develop a healthcare-associated infection. Of course, this correlation may have less to do with procedures inside the ambulance than with what preceded them – for example, lying in a ditch or other unclean environment. “That said, it is all the more important that we design safety into the system; that is, that we construct packaging that assists paramedics in doing their job, to deliver care,” she emphasises.

“Study deliverables included the idea that paramedics many times do not have two hands to accomplish tasks: for instance, to open packaging, or remove a cap or needle-guard,” Bix reports.

Creative thinking is needed, she says, regarding ergonomics for “one-handed users who are also trying to balance as they bump along the road under sometimes extreme conditions of stress”.

But there is a need, too, for labelling which prioritizes the information that the healthcare professional is most desperately in need of. “This could be product type and size, latex status, sterility status and expiration dating, according to some of the work we’ve done,” Bix explains.

“Label designers need to consider how the storage environment, such as a jump-bag in the world of paramedics, can constrain the ability of the provider to utilize the information,” she points out, noting that when using a jump-bag, a paramedic may only be able to view the very end of the box.

Eye-tracking insights

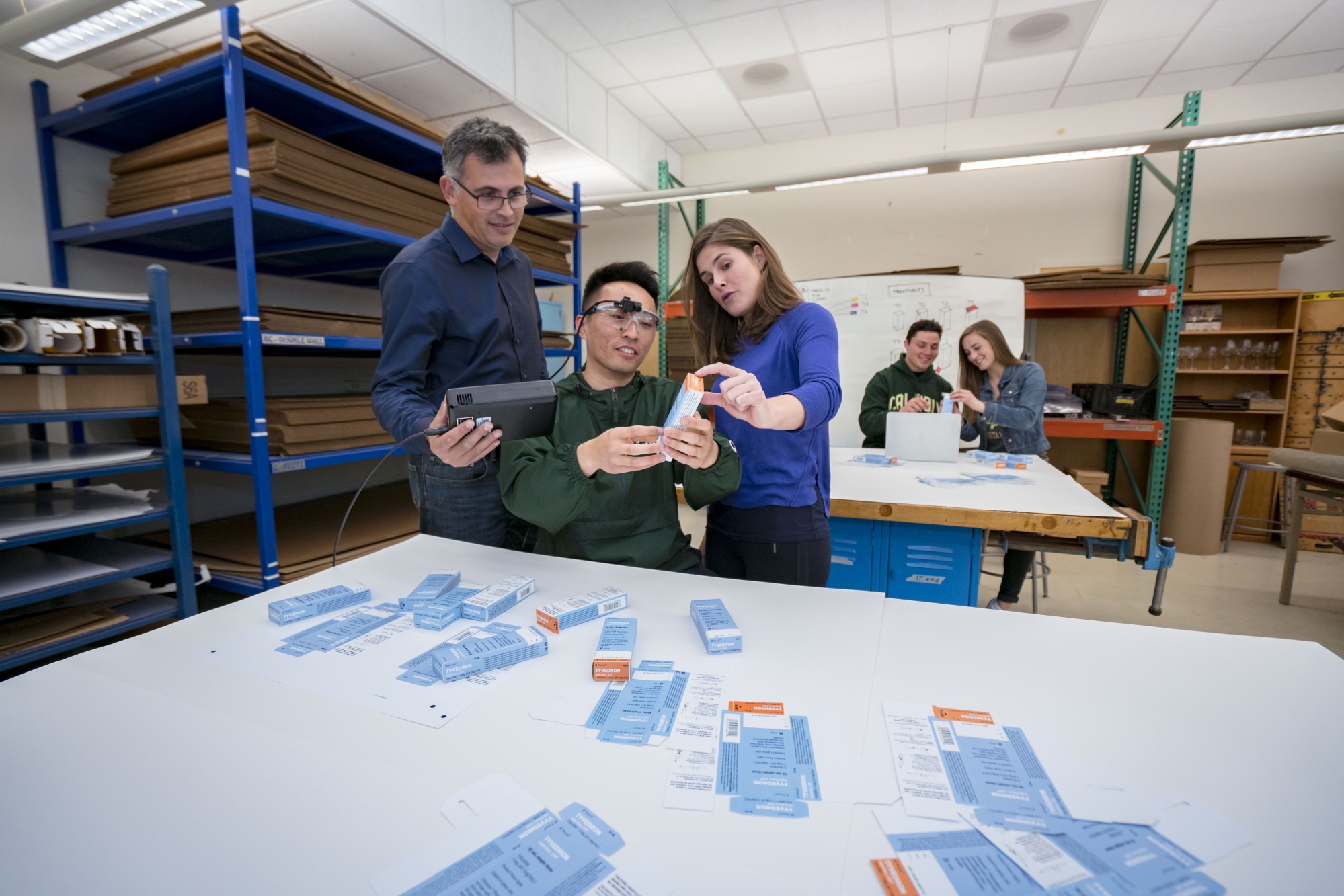

At Cal Poly, as well as affordances and design-thinking pedagogy, de la Fuente’s research team is working on design heuristics for innovation and eye-tracking metrics. “These four areas are closely related to the new ISO 11607 regulation, which includes requirements for usability evaluations for the aseptic presentation of packaging for terminally-sterilized medical devices,” he says.

Team member Irene Carbonell received the award for most promising research at last year’s IAPRI Symposium in Enschede for a presentation on an eye-tracking project.

“We’ve found that mathematical models using fixations and saccades, coupled with the right algorithms, can detect in real-time both when usability problems are happening and the magnitude of the issues,” de la Fuente says. This type of event-detection technology can automate problem detection and so significantly reduce the processing time of eye-tracking data in usability trials, he adds.

When it comes to affordances, he says: “We’ve been using crash-cart medicine packaging to study the effect of design features such as shape, colour, opening location and opening mechanisms in usability performance measures. We’ve found that current commercial packages for crash-cart medications – those typically found in emergency rooms – have poor usability, are counterintuitive and prone to errors, even for healthcare professionals with experience.”

Front-of-pack warnings

For over-the-counter (OTC) medications, the human factors and contexts influencing labelling priorities are clearly going to be very different. A team bringing together packaging technologists from MSU, cognitive psychologists and pharmacists is in the second year of a seven-year series of studies into the efficacy of front-of-pack (FOP) warning labels, Bix reports.

She describes this work as being essentially a “technology transfer” from the better-researched area of FOP labelling in food. The work has centred on older adults, where there is a heightened risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), thanks to a number of overlapping factors including (but not only) perception and cognition.

“We have completed three studies, and were halfway through the fourth, when the novel coronavirus shut down all work with human research participants,” Bix says. “Our preliminary analysis suggests that the benefits apparent with [FOP information] with food products will hold for medications.”

Child resistance in pharmaceutical packaging has long been a concern, and in the US, efforts to make medicines safer for children have developed in the form of a significant private/public partnership. The PROTECT and PROTECT Rx initiatives have brought together industry, academia and government in an effort to reduce the number of children under five accessing OTC and prescription medications.

Today, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are best-known for their work in combatting the coronavirus. But it was the CDC’s director for medication safety Dan Budnitz who led these initiatives, concentrating on three ‘E’s: education; enforcement and engineering. Among examples of engineering solutions has been a ‘flow restrictor’ for liquid paediatric and infant formulations containing paracetamol.

Self-care settings

Meanwhile, in Sweden, Giana Lorenzini has continued her postdoctoral research at Lund University’s Packaging Logistics division, within the Faculty of Engineering, looking at a user-centred approach to pharmaceutical packaging design. Her current two-year project, sponsored by the Kamprad Family Foundation, is investigating the routines of older people taking multiple medicines a day. “I have been reporting their experiences and frustrations with pharma packaging,” she says.

“The traditional way of thinking about packaging only as an additional cost to the product needs to change, so that packaging can be seen in a more holistic manner, as a supportive tool to better care,” says Lorenzini.

Her view is that the pharmaceutical industry’s entire business model might need to change, so that sales are no longer the key criterion of success. As it is, design ideas will often be shelved because they are considered too expensive, she says, or because implementation would add too much time to already long drug development processes.

“The situation would change if companies were paid based on improvements in patient outcomes,” she says. “This would focus more attention on how to develop innovative systems, where the packaging and the intake of medicine are designed to fulfil a patient’s needs.”

This type of model, she says, backed up by a changed political agenda and by regulation, might finally deliver user-centred packaging design.